The Dark Frigate (1924)

The Dark Frigate by Charles Boardman Hawes

Poor Charles Boardman Hawes. In 1922, his sophomore novel, The Great Quest, came runner-up to The Story of Mankind for the inaugural Newbery Medal. By the time he won the prize in 1924, he’d been dead for nearly a year, cut down by a sudden bout of pneumonia. His widow accepted the award on his behalf.

Before his untimely death at age 34, Hawes had truly mastered the art of the maritime adventure novel. He had also, as far as I can tell, never sailed a day in his goddam life. That might be a stretch—born and raised on the east coast, he probably made it out on the water here and there—but unlike his contemporary adventure writers (Melville, London), he was never a sailor or adventurer. Whether that makes him a phony or a genius, I don’t know. It also doesn’t really matter, because The Dark Frigate slaps.

Frigate is the story of Philip Marsham, an orphan whose father taught him the ways of the ocean before being lost at sea. Raised in a tavern and laid up with an unclear illness, young Phil is eventually forced to flee his home and heads for the open sea, where his ship is soon overtaken by pirates. Faced with the choice joining their ranks or walking the plank, he signs up for a lifetime of raping and pillaging.

The Dark Frigate presents a couple of challenges as a children’s book. First and foremost: our hero Phil Marsham disappears for several chapters in the middle of the book. Theoretically, he’s still hanging around the ship, doing boatswain things (whatever the hell that entails). But once we’re in the company of pirate Captain Tom Jordan and his rough and rowdy crew, we hardly see him. Hawes rightfully recognizes that a captured orphan boy isn’t half as interesting as watching the grownups steal ships and slit throats. One of the most memorable passages of the book finds the cook drunkenly concocting a meal so revolting that the crew ends up shackling him to the mast and force-feeding him his own food to torture him. It’s disgusting, frightening, hilarious…and our protagonist is nowhere to be seen.

The other main challenge for children reading the book is that it’s borderline unintelligible. Hawes was a well-bred, WASPy man of letters—after graduating from Bowdoin College and attending Harvard for a year, he made a career of writing and editing for magazines and monthlies. (Nautical novels were his side gig.) No doubt his education served him well, as the language in The Dark Frigate is ravishing. But it’s also remarkably dense, full of seafaring jargon and antiquated prose that reads as pure poetry but requires constant Googling to decipher.

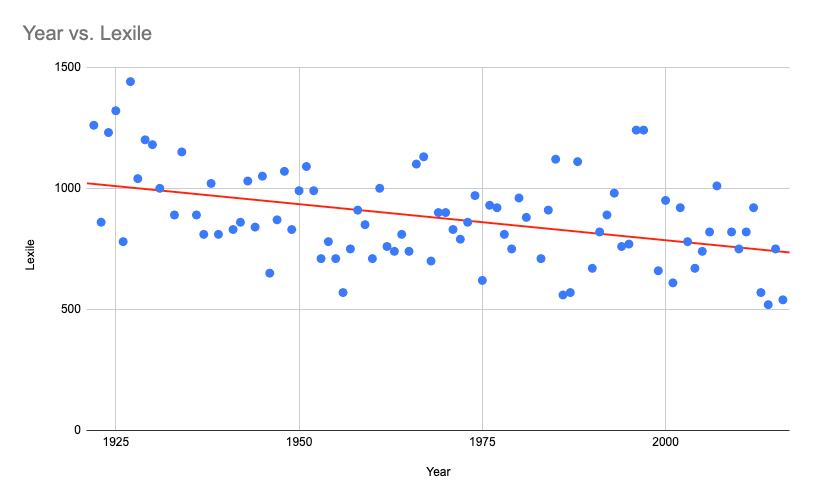

Which brings me back to a central issue with the Newbery books—accessibility. What kids are meant to read these books, and why are these books chosen to represent the “most distinguished” of the year if most children can’t understand them? Wanting to test a theory, I plotted the Lexile levels of all the Newberry winners year-over-year:

There’s a fairly steady decrease over time of the winners’ Lexile levels, which denotes that the winners are generally getting more readable as time goes on. Is this because American kids are getting dumber? Are American authors getting dumber? The Dark Frigate’s Lexile score is one of the highest of all winners at 1230, and I wonder if the selection committee wanted to show off just how “distinguished” a posh Ive Leaguer’s attempt at a children’s book could read. (Then again, my last blog post was an 1140 and I went to a shitty state school, so maybe Hawes’s year at Harvard wasn’t all that important.)

The Dark Frigate begs the question: what makes a book qualify as children’s literature? It’s written just as fancifully as anything Hawthorne or Melville ever wrote, and yet their works fit squarely in the “serious adult literature” category. With regards to subject matter, Frigate is hardly the stuff of typical children’s books. There’s so much blood on the deck at one point that it stains the boards red. A lady who recently married “casts such a glance [at Philip] that he knew she would philander still.” One of the two children in the book accidentally drowns while being dragged ashore to be buried alive. It’s gnarly, R-rated stuff.

My best guess as to why Frigate made the list instead of Moby-Dick or The Scarlet Letter: any book with a child as the main character counts as kid lit. Never mind that Phil Marsham is a secondary character for most of the book, the framing of Frigate as a child’s experience opens it up to the possibility of being warmly accepted by children in a way that books about adults simply cannot do. Reading The Dark Frigate made me feel like a little boy in the best possible way, and it brought back memories of grabbing Kidnapped and Treasure Island from the library as a kid, hiding the dog-eared copies in my room so my parents wouldn’t know how gruesome some of those passages were. Roping me into the story through a child’s eyes was the key to unlocking that experience for me.

It’s a shame Charles Hawes didn’t live long enough to experience the open seas himself. The Dark Frigate is masterful, and it’s easy to imagine him moving away from children’s adventures and onto more adult-oriented fare. Who knows what awards those phantom classics may have won. For as impressive as The Dark Frigate is, the Newbery almost seems a slight.