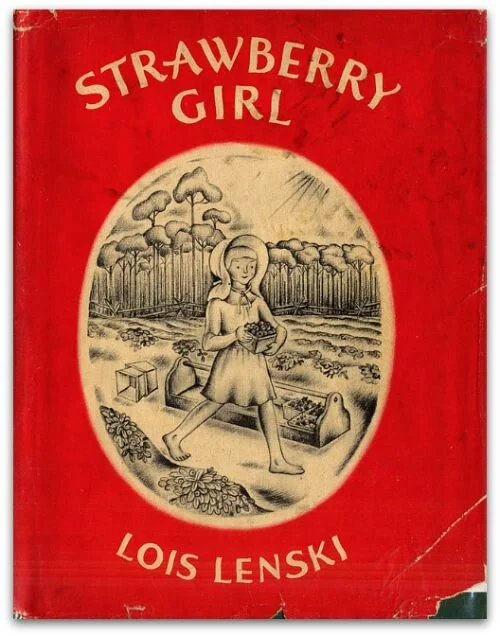

Strawberry Girl (1946)

Florida. Weird state, or the weirdest state? A Google News search of “Florida” today lists these as the top stories:

Lightning strike propels chunk of highway through Florida driver’s windshield

Three South Florida eateries shut for roaches, flies on salad

Florida releases genetically modified mosquitoes in hopes to reduce spread of disease

That’s to say nothing of the alligators, bizarre crimes, and even more bizarre crimes. It’s a massive state that gave us Disney World, Miami Vice, and is home to America’s most-detested former president. In 1946, Lois Lenski sought to bottle Florida’s unique culture in Strawberry Girl. For better and worse, she succeeded wildly.

Strawberry Girl was one in a series of books that Ms. Lenski wrote to explore the myriad regional pockets of (mostly white) American culture in the ‘40s through ‘60s. In Strawberry, the focus is on the early white settlers of Southern Florida, called, I shit you not, “Crackers.” Indeed, these Crackers were the originators of the now probably-racist(?) term used to describe poor white people whose income came from herding livestock. The sound of whips cracking is what gave them their name, but reading Strawberry Girl, you can probably think of a lot of other names poor whites are called today.

After the election of famous Floridian Donald Trump, there were a couple of bestsellers that spurred a short resurgence of the “Poverty Porn” micro-genre, though ostensibly both books were intended to humanize rather than caricaturize their subjects. (Both books are trash IMO FWIW.) It’s definitely possible to produce great art centered on the experience of “plain white trash”—see lots of early country music and The Grapes of Wrath—but it’s also really easy to skip over the line and make something condescending at worst, exploitative at best. And then there’s art that goes so far past that line, it transcends it. “Fancy” by Reba McEntire comes to mind, and so does Strawberry Girl.

In Strawberry Girl, the Boyer family moves from the panhandle down into Southern Florida to start a small farm and ranch business, only to encounter the most stereotypical white trash family you can imagine. The Slaters aren’t cute or cuddly Crackers, but something closer to the inbred serial killers of Deliverance. On the first day of school, two Slater boys show up late to school and beat the teacher so senseless that school gets cancelled for three months. A short time later, Pa Slater burns the school to the ground in a drunken attempt to burn the Boyer’s house to the ground. The Slaters poison the Boyer’s donkey to get revenge for the Boyer’s daring to put up a fence around their yard.

At the time, this was one of the main selling points of Lenski’s regional novels—the supposed “authenticity” of the subject matter that didn’t shy away from the more troubling aspects of real life. But Lenski’s real purpose was something deeper and more personal: she wanted to show things how they really were to help foster empathy for different kinds of people. In the book’s introduction, she writes:

We need to know our country better, to know and understand people different from ourselves, so that we can say: “This is the way these people lived. Because I understand it, I admire and love them.”

It’s a beautiful sentiment. And indeed, Lenski comes sort of close to achieving that through her book. One of the Slater children, called “Shoestring” because of how skinny he is, transforms from a typical childhood bully into an object of pure pity. Main character Birdie Boyer comes to understand that Shoestring’s outbursts are usually related to his alcoholic father’s drunken and abusive antics. Hell, his nickname alludes to the fact that the family is so poor, he only gets to eat a real meal if he can catch it in the swamp. By the end of the book, I learned to love the Slaters (except for their asshole dad) more than the Boyers, who kinda come across as backswamp gentrifiers.

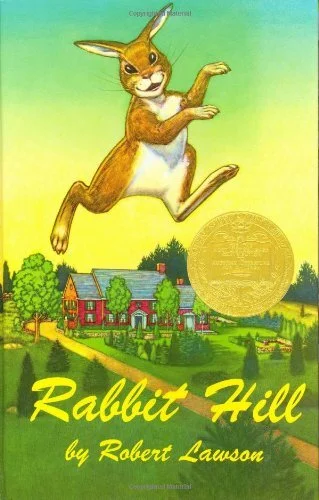

Like Roller Skates before it, Strawberry Girl gave me plenty to chew on with its sincere exploration of complex morality. For example, the Slaters get upset when the Boyers start to fence off their fields because the Slaters have been letting their livestock roam free for three generations. When Mr. Boyer points out that he bought his land and has the right to fence it off, he also points out that the Slaters are squatters, without rights to any of the property their family has been on for generations. That’s objectively a dick move, especially when Boyer threatens to buy up their land or try and purchase the mineral rights underneath it so the family gets displaced. (That’s to say nothing of the casual mention of the Slaters being there since Great-Grandpa Slater stole the land out from under the Seminoles, which…yeah.) For a children’s book, it’s deep, real stuff that our country is still struggling with in some mighty ways today. And as much as I wanted to dismiss the book as hokey or pandering, there’s just too much going on here to swat Strawberry Girl away.

In what’s perhaps the most Floridian turn in the book, Pa Slater gets saved by a traveling preacher and, upon dedicating his life to Christ, becomes a sensible man who respects property rights and stops trying to kill his neighbors. Sure, it’s a stupid ending, but it also seems fitting given the bizarre way Strawberry Girl seems to encapsulate so many seeds that grew into the Florida we know today. It’s not a lost classic by any means, but you could definitely do worse than read this strange little book.