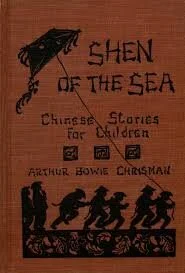

Shen of the Sea (1926)

Shen of the Sea by Arthur Bowie Chrisman

Of the five books recognized by the Newbery Award selection committee in 1925 and 1926, four of them were short story collections, including back-to-back winners Tales from Silver Lands and Shen of the Sea. It’s an interesting pattern to note, but it also has a clear historical precedent. Aesop’s fables are close to 3,000 years old at this point, and Jesus was speaking in parables 1,000 years after that. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Shen and Tales share a couple other surface-level similarities, too. Both are ostensibly collections of fables and folklore from far-off lands, novel reading experiences for American children in the 1920s. And both were written by white authors who had no ethnic connection to the stories they were telling. From a 21st century perspective, it’s a potentially cringe-worthy recipe, as Tales clearly illustrated. And it (again) makes me wrestle with how much weight the “author” credit should carry in both scenarios.

With that said, the two books also provide a startling contrast to each other, mostly because Shen is wildly more successful than Tales as a children’s book. The stories in Tales were rambling, scattered messes that rarely cohered in any sort of intelligible way. In contrast, Shen’s sixteen chapters are all neatly packaged, instantly recognizable in form, and carry a consistently readable voice throughout. They also work as traditional fables—most have a clear kernel of wisdom at their centers, and Chrisman carefully lays out his morals without talking down to his audience. He’s a top-notch storyteller, and while there are a couple of clunkers here, it’s by and large a fun, clever read.

Were it all so simple. To read the book in a modern context is to engage with how these “Chinese stories for children” can be enjoyed as written (and profited from) by someone who was not Chinese, whose culture had been actively abusing and exploiting the culture he was writing about for decades. And so, what bearing should authorship have on the merit (and enjoyment) of art? Because of his ethnic disconnect from the source material, does Chrisman’s collection amount to a problematic level of cultural appropriation?

From what I can find, there are too many unanswered questions to suss out an easy answer. Chief among them: are these actual Chinese folktales and legends? I’m largely ignorant of Chinese culture, but a little quick Googling indicates that at least some of the short stories here are representative of well-known Chinese myths. “The Moon Maiden” bears more than a passing resemblance to the story of Hou Yi. “The Rain King’s Daughter” carries (loose) echoes of Mulan. Others, like “Chop-Sticks”, seem to be complete fabrications, disconnected from the actual legends about the origins of gunpowder, oolong tea, and various other Chinese contributions to world culture.

Assuming Shen is a mixture of some actual Chinese legends, some tales inspired by Chinese legends, and still other stories completely invented in the style of Chinese legends, Chrisman at least avoids the worst of appropriation by offering clear acknowledgement of the stylistic origins of the work. Shen is a totally immersive experience into a very singular type of storytelling, and in that sense, it reminds me of non-Black folks rapping. He’s clearly adopted a medium created by another culture, but he does it without caricaturizing the culture he’s writing about, avoiding a lot of the explicit racism we’ve seen from some of Chrisman’s contemporary Newbery winners. The characters that populate the book run the gamut from wise to foolish, hardworking to lazy, and fill out an impressive array of fables with universal moral wisdom.

Another big question mark over the book’s relation to cultural appropriation is the author himself, Arthur Bowie Chrisman. Unlike Charles Finger, Chrisman never went to the lands he wrote about. Instead, he was a scholar, spending years studying Chinese history and ancient texts, supposedly at the feet of Chinese immigrants living in the United States. As an author, he’s completely absent from the book, never offering any commentary on the tales he’s telling or explaining their origins outside of a general “these were passed down to me” statement on the inside jacket. As a person, he’s nearly completely absent from history. Chrisman released only a couple other books during his lifetime, wasn’t often seen in public, and died an enigmatic recluse in 1953.

It’s also, though, ultimately a work of art that financially benefitted its white author through the explicit appropriation of another culture’s style and stories. There were plenty of Chinese Americans who could have written their own collection at the time, though anti-Chinese sentiment in the US likely would’ve prohibited those authors from getting the same exposure or recognition as Chrisman achieved. In 2021, that feels weird.

Removed from context and taking the book purely on its own merits, it’s one of the winners I’ve most enjoyed. More than almost anything else up to this point, Shen was clearly written with children in mind, simple stories with clear life lessons that go down easy as bedtime reading. I don’t think anyone’s going to come away with a thorough understanding of Chinese culture, but that’s also not the point of the book. Its mastery lies in the presentation and sharp writing, and as a collection of tales, it’s a slight, charming success.

Like most all the Newbery winners thus far, Shen of the Sea wasn’t a book I’d heard of before starting this project, and its cultural impact seems minor as compared to something like Dr. Doolittle. But for readers able to grapple with the questions of authorship and intercultural exchange, it’s an enjoyable read.