Smoky the Cowhorse (1927)

Smoky the Cowhorse by Will James

When Will James published Smoky the Cowhorse, he considered it a straight-up western, and was legitimately shocked to see the book embraced and awarded as children’s literature. (The first copies were just text, but later runs were filled out with his own beautiful illustrations.) James’s life certainly doesn’t have the markings of a traditionally celebrated children’s author—he spent a year in Nevada State Penitentiary for rustlin’ (aka stealing) cattle, moved around between stunt work and the Army, and developed a serious drinking problem that sent him to the grave at age 50. But amongst all that, he found his niche illustrating posters for rodeos across the West. Illustrating, a skill he’d nurtured during his time in prison, eventually led him toward writing short stories to hang his pictures on. Smoky was his first novel, and it was a hit.

Let’s get this out of the way: I’m a sucker for westerns. Give me a boy and a horse and a gun, and I’m pretty much sold. Several years removed from living in the southwest, there’s an aura of nostalgia for the endless deserts, blown-out sunsets, and loneliness of empty spaces. I used to volunteer at a horse rescue, and even though I spent most shifts shoveling shit for hours on end, it was a thrill to be around such gorgeous, majestic animals. My great-grandfather was trampled to death by horses, and though I never met him, it’s a terrifying, haunting image that I haven’t been able to shake since I was a child. There’s power in them animals, and there’s power in them narratives.

You’d think, then, that Smoky the Cowhorse would be right up my alley, and you’d be right. Will James’s novel is simply about a horse, and it follows Smoky from birth through not-quite-end of life. For some readers, this isn’t enough to carry the story—though there is a touching central relationship between Smoky and one of his handlers, Clint, the first half of the book is purty much just one mosey after another. Unless kids are super into horses, there are only a couple of chapters in the whole book that would make any sort of impression, and James makes sure to take the longest route possible to each flash of excitement. Even when the narrative picks up in the back half of the book (Smoky is stolen, rebranded as a shit-kicking man killer, then declines to the point of being sold for chicken feed before his eventual rescue), there’s no momentum to keep you turning pages.

What does keep you turning pages in Smoky, then, is the language. Will James was an honest-to-God cowboy, born in French Canada and home on the range after his parents left him orphaned at age four. Those years spent on the prairies of Saskatchewan (and eventually the United States) gave him sharp insight into wrangler elocution, and the whole book is told with a folksy, authentic drawl that’s completely transportive.

The long spring days followed by the warmer summer days of middle summer had took away all signs of snow excepting where the peaks was highest and the canyons deep and narrow. Up there was crusted hunks still holding out against the sun and hugging the shady sides of rocky ledges, and leaving out moisture that kept the springs and creeks running to the flats below.

It’s mesmerizing poetry.

Alas, there’s another trope typical of westerns that’s disturbingly obvious in Smoky: racism. I knew coming into this challenge that racism would be a recurring theme—honestly, it was one of the main motivators of my taking on the Newbery books, to see how the selection committee’s views changed over time. We’ve already seen some ugly stereotypes, cultural appropriation, and whole narratives committed to rationalizing colonization, but Smoky is shocking in its explicitly racist language. Smoky is stolen by a Black/Latinx man who is only referred to as “the halfbreed” or “the breed”. (I literally gasped the first time I read it.) Eventually, Smoky is sold to an abusive hispanic man, who in a moment of supposed-narrative triumph is whipped in the street by a passerby for mistreating the horse. He’s only saved because the sheriff points out that they’d have to arrest the white man for murder if he dies: “Don’t scatter that hombre’s remains too much, you know we got to keep record of that kind the same as if it was a white man, and I don’t want to be looking all over the streets to find out who he was.”

Some readers of the book have made the argument that the explicit racism in Smoky isn’t worth tossing the baby out with the bathwater, that it can be used to spur discussions with kids about how times and attitudes have changed, to which I respectfully say: horseshit. There’s nothing to have a dialogue about with the racism in Smoky—it’s casual, tossed-off, ugly and obvious in its reductionist attitudes toward nonwhite characters. At least one future Newbery medalist deals with race in a way that can actually facilitate meaningful conversation (and doesn’t normalize calling people “halfbreed”). Hell, Huckleberry Finn was 40 years old by this point, and it’s a much more complex, intentionally considered book to use for those discussions. The racism in Smoky is direct and appalling.

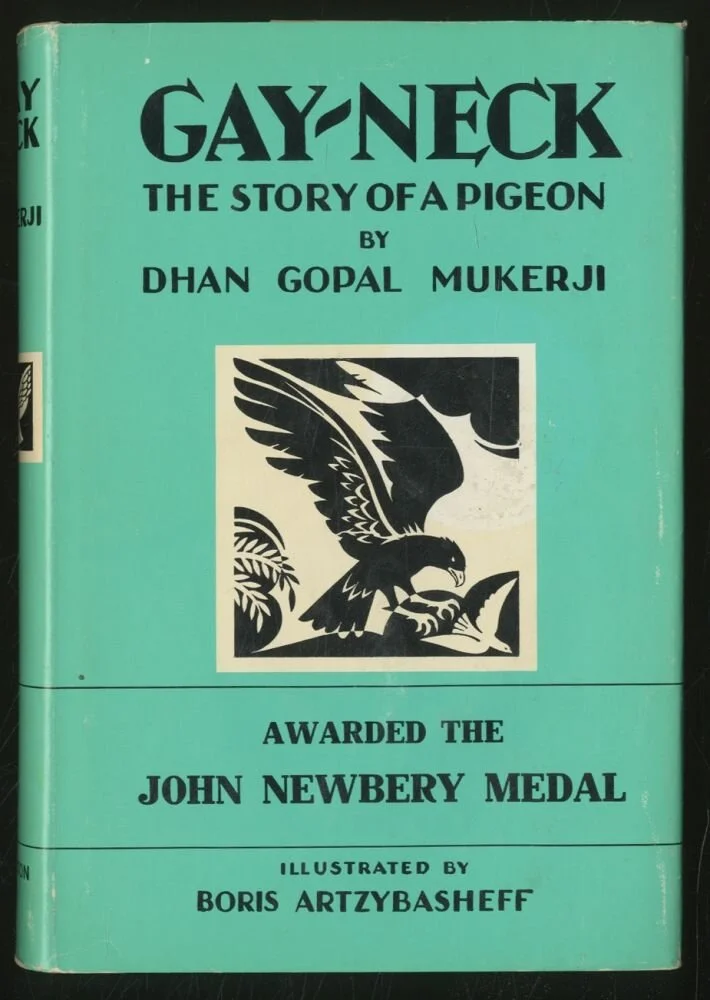

And so, the small pleasures of Smoky are curdled by inexcusable, horrific language. But Smoky also marks the end of an era—in 1928, the Newbery Medal went to its first author of color. The book is called Gay-Neck. Color me excited.